Organisations that support veterans in recovery from addiction, trauma, and mental health challenges often operate with important missions and compassionate intentions. They work to alleviate suffering, rebuild lives and remind the wider public that behind every uniform is a human being who may carry invisible scars long after service ends. However, as noble as these intentions may be, a dangerous practice has become increasingly common: using veterans who are still in recovery as public faces, promotional tools or symbolic success stories for charitable campaigns and fundraising efforts. Although this strategy might appear effective on the surface, it exposes vulnerable individuals to emotional pressure, public scrutiny and psychological risks that can jeopardise their fragile healing process. The cost of relapse, shame or emotional collapse can be devastating, and the responsibility for these outcomes lies squarely with organisations that place their own promotional needs ahead of the long-term well-being of the people they claim to protect.

The recovery process, whether from SUDs, trauma, or a combination of both, is delicate and non-linear. Veterans returning from environments shaped by war, service-related injury, moral injury or loss often carry profound emotional burdens. When substance use becomes a coping mechanism, the journey toward sobriety is even more complicated. Recovery requires stability, safety and a sense of personal agency. When recovering veterans are brought into the public eye to promote an organisation, talk about their trauma or present themselves as examples of success, the process of recovery becomes entangled with performance. Instead of healing privately and at their own pace, they are subtly encouraged to embody a narrative of triumph, resilience and progress long before it may actually be true. This shift turns their personal healing into a public display, which can distort their sense of identity and put them at risk of relapse when the pressure becomes too heavy.

In many cases, organisations do not intend to exploit these individuals maliciously. They may genuinely believe that showcasing a recovering veteran will inspire donors, highlight the importance of their work and help reduce stigma around addiction. But the unintended result is that the veteran’s recovery becomes instrumentalised, treated as a tool rather than a deeply personal, vulnerable and ongoing process. The pressure to maintain the image of a “success story” can be suffocating, especially for someone who may already feel undeserving, ashamed or fearful of slipping backward. When a recovering individual is publicly celebrated, they are also publicly exposed. Any sign of struggle becomes not a private battle but a perceived failure in the eyes of the supporters who were encouraged to see them as an emblem of improvement.

For a veteran who has spent years operating under the rigid structures of institutional life, including military discipline, the added pressure to perform recovery in a specific way can trigger familiar patterns of perfectionism and suppression. Many veterans already struggle with guilt, moral injury or shame related to their experiences in service. When an organisation elevates them into the spotlight, these unhealed wounds may deepen as they feel compelled to live up to expectations that do not align with the slow and uneven nature of real healing. They may smile on stage while feeling broken inside. They may repeat a story that still haunts them. They may downplay their ongoing struggles because the organisation celebrates them as someone who has already overcome the worst. The demand to appear “better” than they truly feel can become a heavy emotional burden.

One of the greatest dangers in using recovering veterans for promotional purposes is the increased risk of relapse. Addiction thrives in conditions of stress, shame and emotional overload, all of which are amplified by public exposure. Even when a veteran wholeheartedly wants to help an organisation, the act of publicly recounting past traumas, discussing periods of addiction or facing crowds can trigger intense psychological distress. These triggers can activate cravings or emotional spirals that undermine the progress they have struggled so hard to achieve. The recovery process is highly susceptible to disruption, and the very act of being used as a spokesperson can inadvertently destabilise the veteran’s recovery foundation. What appears to the audience as a brave testimony may feel to the speaker like an emotionally destabilising ordeal that reopens wounds they were not ready to revisit.

The shame associated with relapse can be catastrophic, especially when the individual has been held up as a symbol of success. Shame is one of the most corrosive emotional states for someone in recovery. It feeds secrecy, isolation and self-destruction. If a veteran who has been publicly featured by an organisation later relapses, the fallout can be devastating. They may feel that they have let down not only themselves but the organisation, the public and even other veterans who looked to them for inspiration. Instead of reaching out for help, they may withdraw out of fear of disappointing those who have celebrated them. This isolation can deepen their despair and drive them into further substance use as a way to numb the emotional pain. The consequences can escalate quickly when shame replaces support, and the person internalises the idea that they are a failure because their recovery did not fit the tidy narrative others demanded.

The potential for tragedy becomes especially alarming when considering the intersection of relapse, shame and suicide risk. Veterans are already statistically more vulnerable to suicide due to the cumulative effects of trauma, identity loss after service, social isolation and untreated mental health conditions. When a recovering veteran is placed in a public role that amplifies pressure and suppresses their true emotional state, the risk of suicidal thoughts can increase. Feeling trapped between the expectations placed on them and their internal struggles, they may interpret relapse as proof they are beyond help. In some cases, this crushing weight leads individuals to contemplate or attempt self-harm. The organisation may continue promoting its work while being unaware of the internal crisis unfolding in the very person they put forward as a success story. The cost of such oversight is immeasurable.

Beyond suicide risk, relapse for someone recovering from substance addiction can also have fatal physical consequences. The risk of overdose is particularly high after a period of sobriety because the body’s tolerance decreases. A single lapse can result in an unintentional overdose that becomes deadly before help can intervene. When a recovering veteran relapses due to the emotional strain of being used for organisational promotion, the stakes are not only psychological but life-threatening. An overdose that results from such pressure is not just a personal tragedy but a systemic failure by an organisation that overlooked the veteran’s fragile state in favour of public recognition. The same applies to the risk of drug-related medical crises, accidental poisoning or alcohol-related harm. A relapse does not need to be long-term to be dangerous; a single overwhelmed moment can cause irreversible consequences.

Another subtle but damaging outcome of this practice is the sense of exclusion it creates when the veteran’s struggles no longer align with the organisation’s expectations. Many organisations highlight recovering veterans during promotional campaigns as long as they embody a narrative of improvement, gratitude and progress. But if that veteran begins to struggle again, their story becomes less convenient. They may be quietly dropped from marketing materials or no longer invited to speak. This unspoken rejection reinforces the painful belief that they only have value when they are doing well, smiling publicly and living up to the heroic image imposed upon them. Once they no longer serve that purpose, they may feel discarded, unseen and unworthy of continued support. For someone already grappling with trauma and addiction, this betrayal can intensify feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness.

This pattern of conditional inclusion reveals a deeper ethical issue: the organisation’s priority becomes its own image rather than the holistic well-being of the veteran. When organisations display recovering addicts as proof of their effectiveness, they risk treating human struggles as marketing assets. The veteran’s trauma and addiction, which should be handled with care and confidentiality, become tools for fundraising. Their recovery becomes a spectacle, performed not for their own healing but to inspire donations or praise. This dynamic strips them of autonomy and reduces their complex life story to a neatly packaged testimonial that benefits the organisation more than the individual. Such instrumentalisation of human suffering is incompatible with true support, compassion and ethical responsibility.

In many cases, veterans may agree to participate because they feel indebted to the organisation that helped them. This sense of obligation can be exploited, even unintentionally. A veteran may feel pressured to say yes when asked to speak at events or appear in promotional materials because they believe refusing would seem ungrateful. This dynamic recreates the rigid expectations of military life, where refusing a request is unthinkable. But recovery requires the cultivation of personal boundaries, autonomy and the right to say no without guilt. When organisations rely on veterans to promote their efforts, they risk undermining these essential aspects of recovery by reinforcing people-pleasing behaviour, compliance and self-sacrifice. The veteran becomes more concerned with meeting external expectations than attending to their own healing needs.

There is also the risk of emotional exploitation when organisations encourage veterans to share deeply personal or traumatic experiences publicly. The retelling of trauma in settings that are not therapeutic can cause re-traumatisation, especially when the audience is large, unfamiliar or emotionally distant. Painful memories may resurface with intensity, triggering flashbacks, panic attacks or emotional shutdowns. When trauma is commodified for public consumption, the veteran’s pain becomes entertainment or inspiration for others. This dynamic can feel dehumanising and may intensify symptoms of post-traumatic stress. Instead of processing trauma safely with trained clinicians, the veteran is encouraged to expose open wounds to strangers, which can prolong recovery or cause regression.

Even in cases where the veteran initially feels empowered to tell their story, the long-term consequences may not be fully understood. Public disclosure of addiction and trauma can limit future employment opportunities, affect personal relationships, or create a permanent public record of deeply private experiences. These long-term impacts are rarely explained to the individual before they agree to appear in promotional content. An organisation may benefit immediately from the moving testimony, but the veteran must live with the permanent exposure of their most vulnerable moments. The imbalance of power and long-term risk makes this practice ethically questionable.

Furthermore, this approach reinforces harmful stereotypes about veterans and addiction. It implies that the only stories worth telling are those with neat, uplifting arcs that conclude with gratitude toward the supporting organisation. Real recovery is not linear and does not always fit a feel-good narrative. When organisations spotlight only veterans who appear to be thriving, they contribute to unrealistic public expectations and marginalise those who are still struggling or who have relapsed. This not only harms the selected spokesperson but also creates pressure for other veterans within the organisation who may feel inferior or ashamed if their own recovery does not match the publicly celebrated version. It fosters a culture in which struggle is hidden, vulnerability is masked and authenticity is sacrificed.

In addition to the psychological risks, using recovering veterans for promotional purposes can strain their social support networks. Friends, family members and peers who witness the veteran’s public exposure may feel uncertain about how to support them. They may assume the veteran is doing better than they actually are because the organisation has presented them as a success story. This can leave the veteran without the support they need during vulnerable moments, particularly if shame prevents them from admitting they are struggling. Social support is one of the most important protective factors in recovery, and distorting the veteran’s public image can inadvertently weaken that support system.

The ethical responsibility of organisations that serve veterans extends far beyond financial survival or public perception. Their primary duty is to protect the dignity, privacy and long-term well-being of those who trust them during their most vulnerable times. When organisations prioritise fundraising or public recognition over these responsibilities, they betray the trust that is essential for effective care. A truly ethical organisation recognises that healing cannot be rushed or displayed for public consumption. It prioritises confidentiality, emotional safety and the individual’s right to recover in private without being turned into an example or a spectacle.

Instead of using recovering veterans as promotional tools, organisations should focus on empowering them to heal, grow and rebuild their lives away from the pressures of public scrutiny. They should invest in qualified staff, trauma-informed care and long-term support rather than marketing narratives. They should create environments where veterans feel safe to be honest about their struggles without worrying about disappointing donors or tarnishing the organisation’s image. They should recognise that the most meaningful successes in recovery often happen quietly, without applause, and that these quiet victories are just as valuable as the dramatic stories that attract public attention.

When organisations step back from the temptation to showcase recovery as a marketing strategy, they make room for veterans to reclaim their autonomy. Healing becomes a personal journey rather than a public performance. Relapse becomes a learning experience rather than a source of shame. Support is offered unconditionally, not based on whether the veteran continues to serve the organisation’s promotional interests. This approach not only protects vulnerable individuals but also strengthens the integrity of the organisation itself.

Ultimately, veterans in recovery deserve more than to be used as symbols of organisational success. They deserve safety, respect, privacy and genuine care. They deserve to be seen as whole human beings rather than inspirational props. When they are placed in the spotlight prematurely, they face increased risks of emotional deterioration, relapse, shame, exclusion, suicide and overdose. These risks are too great to justify any potential gain for the organisation. True service requires prioritising the well-being of the veteran above any publicity or fundraising goals. It means recognising that some stories are too delicate, too personal and too unfinished to be shared with the world. The role of a responsible organisation is not to display recovering veterans but to quietly support them as they rebuild their lives at their own pace, without pressure, expectation or exposure.

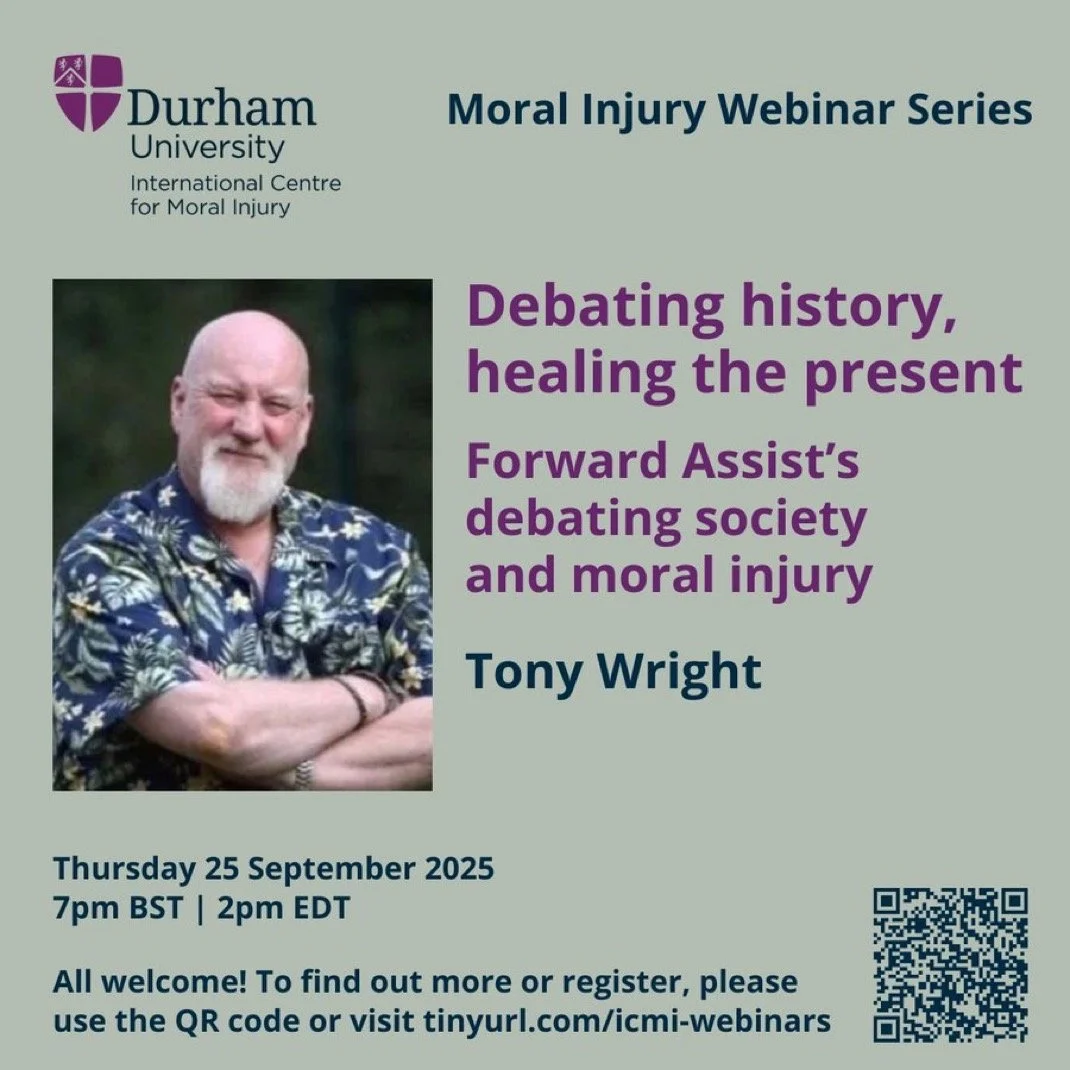

Tony Wright